Behold a White Horse

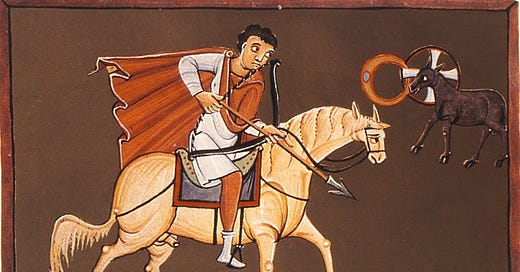

And I saw, and behold a white horse: and he that sat upon him had a bow; and a crown was given unto him: and he went forth conquering, and to conquer.

1.

Spring had come, and with it, war; and Stephanakios, Duke of Syria, felt a love for life he had not felt in years.

The duke wasn’t yet an old man, but he was an aging man, and he gave thanks to God for the chance to go to war again, having long assumed he would die in the twin tyrannical grips of Peace and Pleasure. Stephanakios wasn’t a violent man, in that he wept at the suffering of Christians, but he was a man who derived a great sense of adventure from the rape and massacre of heathen peoples. He was, in short, a man who loved his country and his god; two entities he knew to be as just and wise as they were eternal. Peace was to him a war so long as he lived in a world divided, and Pleasure a cancer to nations. War, he felt, was the only cure to both.

Stephanakios wasn’t sure why or how the war had actually begun. There were vague pretenses about land and other ancient offenses, but the duke needed little justification. On one side was the Roman commonwealth, and therefore the one true Mother Church; on the other was the ancient tyranny of the Sassanids, a nation of fire-worshipping infidels. There was no choice for a pious and contemplative man like Stephanakios. He would serve Christ’s terrestrial kingdom until it covered the surface of the world or die in that pursuit.

All that gave the duke some pause was the fact the emperor had appointed a new Master of Soldiers. This news initially delighted Stephanakios. The senate was littered with men he would have given anything to serve. But instead of any of the great patricians who had given decades of service to Christ and the state, the emperor had chosen a young staff officer with no wartime experience. The duke’s contacts in Constantinople told him the man’s name was Belisarius, that he came from a military background, and that he had served in the imperial guard for a little over four years before the emperor grabbed him from total obscurity and vested him with supreme military power.

It was unusual, but not without precedent. Nobody had ever heard of the emperor’s predecessor before he was acclaimed autocrat by the senate, people, and army. But more importantly, the duke took comfort in the knowledge that the emperor was the rightful and supreme lord of all the nations of the world and was therefore guided by divine and perfect wisdom. His word was natural law. It preceded all form in the universe and was put into language alone by his decree. This war, its birth, and its ultimate conclusion had all been set at the first breath of Time. Every minor note played its part in the symphony of Creation. With this in mind, Stephanakios gave thanks to God for the chance to meet this mysterious Belisarius, and rushed about the palace throwing open windows and dusting off the paintings on the walls in preparation for the young marshal’s arrival. After many months of delay, Belisarius and his retinue had finally made landfall, and were due within a day.

It wasn’t a minute too soon. Violence was stirring along the frontier, and Stephanakios had already drawn the first blood of the war after confronting a band of the Sassanid shah’s Arabian mercenaries as they torched a village near the town of Apamea. Though thousands of refugees fled toward Antioch in terror after news of the attack had spread, the raid in reality had been conducted by a hundred and thirty half-starved teenagers who took the shah’s commission for a chance to secure something to eat more than anything else. Stephanakios and his retainers slaughtered them to a man, and the Arabians’ heads, hands, and genitals were nailed to boards and carried in triumph through the cheering streets of Antioch.

While he pined every day for another chance to whet the blade of his piety, Stephanakios found his short time of public glory interrupted by a number of monotonous bureaucratic concerns that quickly sucked up all of his time and attention. Soldiers and horses had to be fed, and their food and fodder was carried on the march. The movement of supplies required additional personnel and pack animals, who in turn had to be fed, which therefore required more oxen and wagons, more people to drive them, and so on until some kind of equilibrium was achieved. This all required money, which therefore required accountants, clerks to keep their paperwork, and scribes to issue orders and write contracts and bills of sale. Those documents were usually drafted, proofed, and dictated by attorneys, who also ensured all operations were up to church, civil, and military law. These people all in turn needed to be fed, moved, and paid, which then, of course, caused further complications. Since these clerks, accountants, scribes, and attorneys were all of soft patrician upbringings, they each came with slaves and other creature comforts that needed to be moved and fed. And so on. Stephanakios found it all tedious and low, and not in the least bit noble, but he supposed (with some regret) that it was necessary for the war effort and therefore the virtuous, Christian thing to do.

The streets of Antioch were thrumming as they did in the throes of Saturnalia. Soldiers were everywhere, squatting in the gutters and spilling from the drinking halls as they poured their pockets on the people of the city. Monumental wagon trains carrying tens of thousands of tons of grain and fodder and other needed supplies had strangled the highway north to Tarsos, and a flea-ridden shantytown of mercenaries, merchants, and prostitutes had established itself all along the field outside the city where the army sat encamped. The Ram’s Gate in the west and the Lion’s Gate in the east were choked with traveling merchants hawking sheets of silk from Serika, mountains of multicolored spices from the lands beyond the Indos, Aksumite ivory, fine cloth slippers, and rugs with detail stitched in gold. There were lions, peacocks, and all manner of caged exotic animals for sale, and craftsmen with experience in mosaics announced themselves from the gutter, calling out the names of famous churches where they had done the floors or portraits on the walls. Coins rang and sang as they passed from hand to hand to teeth and pocket, and fortunes were made at the cursory wave of a quartermaster’s hand. For the first time in years, the imperial coffers poured their bounties on the people, who sang and danced and praised the war and the love of their gentle benefactor, the worshipful Duke Stephanakios. There were men selling boots, new saddles, fresh socks, and whatever else a soldier might have worn out on the march. Others pushed carts through the strangled streets, all stacked high with sweet breads, jars of local wine, and salted fish and pork. Herdsmen came in from the countryside with long chains of bleating goats and snorting hogs in tow, and fishermen bore up vast racks of catch with scales still wet and gleaming from the river. Horse tamers had established enormous camps along the banks of the Orontes, all of which were full of half-wild stallions from the far-flung wastes of Parthia and Arabia. These men crowed in a dozen different frontier dialects as they waved their hands and touted the fantastic strength and intelligence of the beasts in their pens. Meanwhile, ravenous brigades of prostitutes stalked up and down the boulevards of Antioch, shaking their skirts and calling at the soldiers passing by. They came in every shape, size, color, age, and gender, and many found supplemental work as translators, cooks, and porters when the men grew tired of their charms. Most came with masters dressed in gaudy silks and jewels, but a nearly equal number were hardy entrepreneurs, having come on foot from all throughout the diocese, stopping only to wash their rags and bodies in the Orontes before descending on the city. They often had great flocks of bastards trotting along behind them, who many happily pawned off on the soldiers for an extra copper bit. As soon as the money or the soldiers’ vigor started drying up, these men and women would disperse, a fresh generation of recruits for the Army of the East already stewing in a thousand fertile wombs.

Stephanakios found it all distasteful. Just as he feared, the common man was driven only by thoughts of what to eat or fuck. War with the infidel was a sacred thing. There were few acts God loved more than the systematic eradication of non-Christian peoples, and the duke had always felt that a man of upright Roman character — a man animated by virtue and guided by the moral order of Creation — could do nothing but scoff at base and earthly pleasures. But to the duke’s great embarrassment, the men of the Army of the East not only hungrily engaged with prostitutes, but also bought anything and everything they took a fleeting interest in. Hardened veterans with missing eyes and mangled jaws spilled their wallets to have their fingernails painted or boot laces tied. The duke found it all incredibly crass, and thought for a moment that war was wasted on the poor. But then he reminded himself that war would be impossible without the poor, and was forced to admit, once again, that perhaps it was all for the best.

The whole idea depressed him. Homer never mentioned accounting summaries, bills of sale, or foreign eunuch pleasure boys. For a moment the duke thought that war was just the result of common market forces, and that the whole idea of a “noble war” might be nothing more than a tired old literary device. But then he remembered his own experiences serving in the last eastern war all those many years before, when he stood in command of the phalanx that broke the Sassanid charge outside Amida, turning back the heathen tide for Christ and Christians everywhere. It had been glorious, well and truly glorious; and Stephanakios knew it to be so.

2.

Belisarius had spent his youth on the wind-blasted steppe of the northern frontier, and the simple solitude of those whispering oceans of grass had imparted in him a sense of unease at the scale and noise and smell of urban life. It seemed to him unnatural; unhealthy; a spit in the face of God. But beyond all that, Belisarius knew that places of great prosperity could not exist without great iniquity, and as he caught his first glimpse of Antioch, he shuddered to imagine all the many millions who labored and died in anonymity to give the people of that city their lavish baths and theaters and monuments.

Antioch sat at a bend in the Orontes where the river split and wrapped around a liver-shaped island before joining again and flowing to the sea. Bridges connected this island to the river’s western bank and the larger part of the city, which sprawled in the space between the eastern bank and the soaring wall-like slopes of Mount Silpios. Even from a distance, Belisarius could see magnificent mansions with private bath houses, opulent chapels, and gardens fat with pear and pomegranate trees, where aristocratic children sat in the shade on hot summer days, learning Homer and the deeds of the saints by heart. Broad avenues busy with life stitched across the city, and smoke from thousands of chimneys buried everything in a gray, gleaming smog. A twenty-foot high stone wall ran along the riverbank and hemmed the mainland side of the city against the mountain’s steep and grassy slope. Another, smaller branch of fortifications ran along the length of the mountain’s narrow ridge, and a small stone fortress stood atop the summit. A banner adorned with an icon of the Mother of God fluttered from its parapets.

The fields around the city crawled with thousands of slaves who were planting, pruning, and drawing weeds up from the ground with heavy burlap sacks around their necks. They looked up and waved as Belisarius and his men approached, and the landowners rode out on their fine racing stallions to ensure the soldiers kept their distance. They regarded Belisarius and his men with a kind of suspicious contempt he had long grown accustomed to in the perfumed palaces of Constantinople. Any patrician could smell plebeian blood like a hound smelling fear, and Belisarius knew that all those handsome aristocrats could see were his mutt-like features and hands worn with work, or the way he slouched as he rode, or his half-broken barbarian horse, or the tasseled Skythian blanket he used instead of a saddle. He looked more like a slave than any of the famous heroes from their ancient genealogies, and Belisarius knew they already hated him for it.

His father and grandfathers had been soldiers, and some of his earliest memories included learning how to shoot a bow or work a shield. While his peers learned rhetoric and philosophy at ancient academies on the blistered shores of the imperial heartland, grizzled old drill instructors taught Belisarius the only rhetoric he ever thought he would need, and his philosophical education was limited to what he heard in church and what was made apparent by the land. He did not have the temperament for any kind of life outside the saddle, and was horrified when the emperor called him into his gilded presence to invest Belisarius with the rods and staff of supreme imperial power. It meant immersion in a world he didn’t understand and to which he felt he would never truly belong: a world of whispered palace secrets, labyrinthine court ceremonial, and the political mire of ever-changing loyalties. But when Belisarius tried to protest his appointment, the emperor silenced him with a single wave of his globe-turning hand.

“There is no man better for the task,” he said.

Belisarius did not think his promotion was entirely undeserved. He felt he understood the sciences of tactics, logistics, and strategy better than most. He prayed and took communion. He did not drink or overeat and started every morning with a round of calisthenics. He could ride and shoot and wield a sword as well as any other. But there had been about two dozen senior officials in line before him who better deserved the appointment: famous generals who had cut their teeth and earned their fortunes bringing war to the hill people of Isauria, protecting Constantinople from rebellions in Thrace, or campaigning on the dark and distant shores of the Euxine Sea. The youngest of them all was nearly twice his age, and the least well-known still had streets and temples that bore his name in Constantinople.

As Master of Soldiers for the East, Belisarius was the acting theater commander for all military operations from the Bosporos Strait in the west to the Sassanid frontier in the east; and from Armenia in the north to Ethiopia in the south. On top of commanding the field army, which numbered twenty thousand fighting men, he also had a supervisory role over all the many frontier forts and their garrisons and the various provincial militia responsible for safeguarding the nation’s borders. The number of soldiers he was responsible for alone made him sick; and that was without counting all the many thousands of support personnel needed to make an army run. The total figure easily ran into the hundreds of thousands.

But what troubled Belisarius above all was what would happen if he failed. He knew he could not stop disease, nor the rich and powerful from using the weak and poor like cheap old toys. He could not spare women and children the terrors of a home headed by a tyrant, nor could he bring easy lives to the crippled or insane. But he could protect them from the wholesale rape, massacre, and enslavement they would face under the cruel dominion of Conquest. He alone stood between them and ruin. And it was the weight of that responsibility, ultimately, that terrified him.

A pair of sword and jewelry-wearing soldiers came riding up the road from Antioch. Both men had their hair carefully coiffed and their faces clean of beards and wore deep emerald and amber-colored tunics with white silk tights and ebony shoes with heavy silver buckles. They hailed, approached, and dipped their heads in supplication. Belisarius flinched at the overwhelming stink of their perfume.

“Hail and blessings to Flavius Belisarius, our most magnificent Master of Soldiers. Stephanakios, worshipful Duke of Syria, is eager to make your acquaintance,” one of them said. “There are some matters that require your immediate attention.”

“Stephanakios is here?”

“He is, your magnificence.”

“Why?”

3.

Hermogenes, Master of the Offices, was a man few knew and even fewer loved. Long-armed and slender, with leaden eyes and painted wooden teeth, Hermogenes had brought the emperor’s original declaration of war to the Sassanid ambassadors in Antioch and remained ever since, attending plays and feasts and balls with all the noble houses of the city. Whether because of his empty gaze or perfect androgyny, Stephanakios found something about Hermogenes slightly unsettling, and largely avoided him since the day he first arrived. But when the news finally came that Belisarius had made landfall, the duke’s curiosity became too much to bear. He went and asked Hermogenes his opinion of the new field marshal. The Master of the Offices knew Belisarius personally, and also controlled every imperial spy from the foggy gutters of Londinium to the misty depths of the Nile. There wasn’t a single man who knew more about anyone anywhere else in the Christian world, and the eunuch’s eyes lit up at first mention of the marshal’s name.

“Oh, how should I put it?” Hermogenes said. “I’m sure he would be perfect for the role, were he older and of, perhaps, a bit better breeding.”

“Better breeding?”

“I thought you knew!” Hermogenes cooed in his quiet, boyish voice. “It’s all the talk in Constantinople. Yes, the magnificent marshal is of common Thracian stock. Thankfully, our most pious lord lacks the old prejudices shared by many in the senate. But his origins aside, all the imperial peers are in accord that his lack of practical experience might prove detrimental to the war effort. We said as much to our inviolable sovereign, may he always be victorious, but his nobility expressed a higher, deeper wisdom. Such is the grace and piety of our most virtuous augustus. However, I am firm in my belief that Belisarius might have been an … imperfect choice. But then I suppose we must allow him to make a display of his talents before we put our opinion to them!”

“How common?”

“Is the marshal?”

“Yes.”

“Well, let me put it this way: one couldn’t get any more provincial without leaving the provinces entirely. One of the good marshal’s grandfathers was even a Hun, if I’m not mistaken. I believe the other was a Goth.”

This news alarmed Stephanakios, but through the raw power of his Antiochene, Stoic, and Christian convictions, he managed to reserve any final judgement for his initial meeting with the man. After all, it would not be the first time a citizen of exceptional ability had emerged from among the masses. The emperor himself had begun his life as a poor Illyrian swineherd, and the empress a woman of scandalous repute. God was mysterious, and his plan often perplexing, and Stephanakios supposed this was one of the many ways by which the divine encouraged Man to look upon the fabulous machinations of Creation in all their ceaseless glory. This revelation pleased and comforted the duke, and he retired to his garden to meditate upon the matter further.

He spent much of the next week making ready for the marshal’s arrival. A feast would have to be prepared, and it occurred to Stephanakios that anybody used to the utter splendor of Constantinople might find a healthy, conservative, and well-mannered Antiochene supper a little dry and old fashioned, no matter how provincial the person in question might happen to be. He therefore sent for all the great and ancient names of Antioch and the finest pipes of vintage wine from the deepest vaults of the palace. On the day Belisarius was due to arrive, the duke assembled his retainers on the parade ground of the governor’s palace and rushed up and down the lines himself, tightening straps, smoothing tunics, and straightening messy strands of hair. As a final touch of ornamentation, the duke had a dozen of the raiders’ heads he had collected near Apamea coated in tar and mounted on stakes. The ruined forms watched him work with black and vacant stares.

Stephanakios was still hard at work when a trumpet sounded and the first of the marshal’s complement came riding through the gate. The marshal’s retainers, about fifteen-hundred men in all, made up the bulk of the column. These mercenaries had been recruited from across the hardest parts of the country, and because of their high rate of pay, could afford to arm themselves with all the best equipment from the imperial armories in Constantinople. All of them wore iron scale coats over shirts of mail and heavy padded tunics. Their horses were all firmly muscled and energetic, having been raised and broken in the open wilderness north of the Danube river. Trained to fight in every useful style, these men could be deployed as shock troops with a shield and spear or as mounted archers with a bow. They wore large beards or Germanic mustaches and sported strange foreign tattoos and cheap bronze jewelry. The language they spoke was a tongue of their own invention: a barking stew of Latin, Greek, Gothic, and Hunnic alongside an arsenal of harsh barbarian slang.

One large contingent of Huns and another of Heruli had also come with the marshal from Constantinople. There were about six hundred men in each complement, drawn from tribes settled along the northern frontiers. Small men on wild horses, all were leathered from a life in the sun, and their cheeks had been ritually scarred in adolescence to prevent the growth of facial hair. They wore skins blackened by age and the elements and were more graceful on horseback than most men were on their own two feet. Gold flashed on their teeth or in their ears, and every one of them carried tightly-curved bows made from wood and animal bone which, if the stories were true, could easily drive an arrow through shield, armor, and muscle all the way up to the fletching.

Stephanakios was not entirely comfortable serving alongside pagans, much less pagans so savage, but decided that if the emperor – in all his divine, revelatory wisdom – had decided they were helpful to the war effort, he would fight alongside them and be thankful for the chance to do so. Besides, he reasoned, these foreigners were only heathen because they were not Christians yet, and what better way to evangelize than through a display of victorious Christian arms? Granted, a peaceful baptism was always preferable, but even Saint Constantine himself had been convinced of Christ’s everlasting grace through victory in battle.

Another trumpet sounded and the duke looked up in time to see a silk banner marked with an icon of Saint Christophorus carrying Christ across a river. The men who escorted the standard were the marshal’s bodyguards, and they wore purple silk armbands to mark their rank. Stephanakios could immediately tell who among them was Belisarius by his age alone. Short, with the lean and stocky body of a wrestler, Belisarius wore a thick black beard and matching curly hair. He was also younger than the duke expected; only twenty-three or twenty-four years old.

Belisarius leapt off his horse with the grace and agility of a champion charioteer and crossed the yard on the balls of his feet. He wore no armor, nor the purple sash of an officer of the imperial cabinet. Just a cheap linen tunic, faded Hunnic trousers, and a sword in a plain leather scabbard.

“My most glorious master,” Stephanakios said, reaching for the young man’s hand to kiss his ring. He could see Belisarius was filthy from the road, and almost flinched at the smells of campfire, dust, and horse manure emanating from his hand. “Welcome to Antioch.”

“Thank you,” said Belisarius, his tone cold and flat.

“I hope your journey wasn’t too distasteful,” said Stephanakios. “As I’m sure you’ve heard, the infidel has already made a number of intrusions into the lands of our most sacred commonwealth. I met one such force in battle barely fifty miles east of here. Owing to the force of Roman arms and a faith in Christ triumphant, I brought back what remained as a gift to you and the other good companions of our high and sacred sovereign.”

Stephanakios gestured at the tarred and rotten heads. Belisarius cut them a quick, contemptuous glance. After a moment he clicked his tongue at one of the duke’s slaves and gestured at the stakes.

“Take those down,” he said. The boy scurried off to fetch a ladder and Belisarius turned back to the duke. His eyes danced everywhere, meeting anything and everything but the duke’s own gaze. “Why are you here?”

“I’m not sure what your magnificence means.”

“I mean why are you here, in Antioch?” Belisarius hissed, his voice suddenly laced with acid. “You’re nowhere near your sector. Where are your men?”

“Apart from these men here I have two mounted regiments billeted in Epiphania and three more at Beroea.”

“Then you need to go there,” said Belisarius. “You’re their leader. Lead them. By Christ, man. There could be a hundred thousand Persians marching through Syria right now and I wouldn’t even know. Pack your shit and get out there as quickly as you can. And bring your men down from Beroea. They’re no use there. Thank you.”

With that, the marshal stalked off into the palace, asking after his baggage and his quarters. Stephanakios was left leering like a moron in his wake, his back and shoulders rigid at attention. He drummed his fingers on the pommel of his sword. The slave Belisarius ordered to take down the Arabians’ heads had returned with a ladder and was trying to lift the first of the heads off its perch. The tar and rotting gore had formed a kind of glue that fused the fetid mass to the rough wood of the stake and the slave nearly shot from the ladder with surprise when the duke barked out his name.

“Leave it,” Stephanakios commanded.

The slave, worried that he might be the victim of some cruel joke, paused and turned on the ladder with the head’s filthy, tar-covered hair still wrapped around his knuckles. He stared at the duke for a moment, unsure of what to do, until Stephanakios drove him away with an impatient flick of his hand.

On the far side of the yard, Hermogenes stood with his hands in his robes, watching Stephanakios with his cold leaden eyes. Stephanakios nodded and the eunuch bared a curling wooden smile. There was a silent kind of rage in the thin man’s grin, and the duke, uneasy, withdrew inside the palace.

4.

The feast began in the palace garden shortly after midnight. There were dancers and music and dogs performing tricks, and most of the guests were afoot, chatting about the war and the duke’s recent victory, with golden cups of fine local wine splashing in their hands. Others were sprawled across colorful velvet couches with animated conversation leaping from their lips. They marveled at the duke’s well-trained dogs and the grace and refinement of his slaves, and drank toasts to his health and hospitality at every chance they had.

All the town’s elite had come. There were bookish academics and nervous literati engaged in passionate debate about Plato and his compatibility with a well-led Christian life, while young officers and their wives drifted from couple to couple of their kind, reciting a rote ballet of inoffensive comments on the music, weather, and wine. The town councilmen of Antioch were also there in all their regal bearing, draped in silken vestments the color of piss, waving away petitioners with snorts of contempt as they waddled from dish to dish. Their wives and daughters trailed behind, heavy in their rings and ropes of pearls and amulets of glass. Their flowing skirts and cloaks were patterned with polygons or the outlines of flowers or trees or birds taking flight, stitched in profile with gleaming copper thread.

The marshal’s men were also scattered throughout the garden, unsettling the guests and terrifying the slaves. Fara, the lanky copper-haired commander of the Heruli, was blackout drunk and reclined on a couch with a flower in his hair and a pair of comrades in his arms, bellowing a song from the shores of his distant homeland. Octar, commander of the Huns, was engaged in Socratic dialectics with a pair of junior deacons. He sat with his legs crossed and hands together as he listened to the two explain how Christ had been created by, and was of equal substance to, God the father. Meanwhile, the marshal’s bodyguards reigned large and loud over a table near the stable door the duke reserved for slaves. These men were Tobias, the ex-priest; old Andronikos, the one-eyed; Kyrillos, the harelipped; young Taumas, the gap-toothed; and Smallfoot, the Makedonian. They sat in hot and drunken company, crowing in their marching tongue as Constantius, the marshal’s deputy, crushed walnuts with his big scarred fist. Constantius had lived every life a poor man could live, having worked as a miner, a bear tamer, and a galley rower all before becoming a soldier. But before all that, he had begun his life as a slave, responsible for the sweltering and agonizing work of heating the public baths in Constantinople. It was in this capacity, after stealing an extra piece of bread from his master, that Constantius lost his nose. Because of this, he wore a prosthetic nose cast from lead to cover the old wound up, which was in turn fixed to a rusted iron basket he wore around his head. Rot had mangled the corner of his mouth, which pulled it upward in a snarl, and a whistle emanated from the place where his nose used to be. Andronikos and Tobias were pounding the table with laughter at something he had said, while young Taumas, ever the lamb, asked a nearby serving slave if she could please bring them all more wine. Belisarius watched them laugh with envy from afar. Old Andronikos had taught him how to shoot; Smallfoot, the Makedonian, taught him how to ride. It had been Tobias, not some grave patrician bishop, who first convinced Belisarius of God’s existence. They were incapable of irony, judgment, or deception. When he was among those old bandits – those harelipped, one-eyed, tattooed, gap-toothed, poetic, and thuggish brothers in arms – the marshal felt complete.

Belisarius wished more than anything to sit with his companions and revel in their old war stories, but unfortunately, his rank required him to make a certain appearance for all the duke’s distinguished guests. He was the Master of Soldiers; the emperor’s eyes, ears, mouth, and sword. A companion of the Sacred Cabinet. A member of the imperial household. He could not be seen associating with pirates and cutthroat half-barbarians when there were members of ancient patrician dynasties about.

As he always did in Constantinople, Hermogenes had gathered a crowd about himself as he preached about the insidious trappings of human affection. He had exchanged his wooden teeth for a set of yellowed ivory dentures which were, much to the marshal’s shock, somehow more disgusting than the splintered mess that normally formed his smile. His long spindly fingers worked an unseen loom before him as he spoke, and his words seemed to hover where he left them in the air, gathering and smothering all within reach of his breath. The sight gave Belisarius chills. Everybody around him seemed to forget that when the former Master of Soldiers for Thrace was declared emperor by his troops and marched against Constantinople in the summer of 515, Hermogenes stood beside him, serving as the rebel’s personal advisor. Only the full might of the imperial navy had been able to turn them back; yet somehow, through what Belisarius felt must have been some perfect combination of guile, luck, and — perhaps ironically for a eunuch — balls, Hermogenes obtained a pardon and, within a short twelve years, climbed his way up through the palace to become one of the most powerful men in the country. There was no official tally of all the personal enemies Hermogenes had muted, blinded, and banished, but Belisarius was confident that if one of them had the guile, luck, and balls to track down all the eunuch’s other victims, that man would have enough blinded and exiled mutes to march on Constantinople for himself.

So Belisarius kept his distance from the eunuch. He found a bench in a quieter corner of the garden and there sat in silence, watching and waiting for the party to disperse. But to his great horror, more guests appeared as the night wore on. Before too long, the quiet corner of the garden he had staked out for himself was overrun with a horde of the duke’s drunken and distinguished guests. These drifted by Belisarius to kiss his hand and offer their respects. Many commented on his Hunnic eyes or Gothic nose, or the way his hands were rough like the hands of a slave. Some, aware of his close relationship with the emperor, came to Belisarius with imperial petitions. Phokas, a local arms manufacturer, begged Belisarius to please pass along his most sincere and gracious thanks to their supreme lord and sovereign for at last bringing war against the infidel. Mousoulios, self-acclaimed curator of rare and exotic entertainments, said he sold the best girls, boys, and mules in all of Syria. The Patriarch of Antioch, a lifelong politician, was in a wild drunken fury, and Belisarius was forced to listen to the witch-like old man rant long about how the emperor’s exorbitant new tax code had forced him to sell one of his villas on the island of Kypros.

“I mean really,” the patriarch roared with a dramatic and dismissive snort, “How much more does he need?”

“How much more do you need?” Belisarius snapped back.

The patriarch stared at him for a moment, a shiny drop of saliva glistening on the corner of his mouth.

“Don’t think you’re innocent in any of this,” the patriarch said, his face cold and grim. “For what is war but a contest for property?”

Belisarius did not know what to say. He had seen the emperor’s eyes come alive too many times at the idea of a world unified under a single Christian state to think he wanted anything else. A world without division. A world cured of the scourge of war. And if the heathen nations had to be baptized at the point of a sword, Belisarius felt that, within a few generations, their descendants would be happier for it. But the marshal was not a confident communicator, and when he tried to express his beliefs about the emperor’s motivations, the patriarch just sneered and shook his head.

“Acceptance of the Truth can require no compulsion. If our augustus were only interested in spreading the Gospels, why must he make due with palaces, slaves, and a harlot for a wife?”

On the other side of a long row of rose bushes, Stephanakios was holding court at the center of the garden. He was perched like a king in a carved ebony throne, his shoulders thrown back and chest puffed out so much that he resembled a springtime sparrow flaunting for a mate. He had one hand on his cheek like a man in deep and Christian contemplation, and the other on the ruby-studded pommel of his sword. A massive red velvet cloak made him appear bigger than he really was, while a pair of white silk tights and small ivory slippers revealed a petite and boyish frame beneath. A dozen guests surrounded him, all vying for attention like the suitors of a young and wealthy widow. The duke seemed to revel in it all, laughing with might at their tired, flaccid jokes.

“Well, our God is mysterious,” he bellowed, “but I’d not have it any other way! The cultic practices of our pre-enlightened ancestors were so transparent one wonders how they failed to see the utter falsity of their beliefs! It is indeed a better age, and I am thankful for it. But these Arabians — much like those I left on the fields of Apamea, carrion for the birds — these savages live and fight like animals, more out of hunger or necessity than divine and sacred purpose. Just as one must euthanize a hound whose mouth begins to foam, one must also eradicate these ruffians before they cause harm to those living in the light and goodness of the Lord. Indeed, our God is just. I thank him daily that I might ease the spiritual suffering of the heathen while also seeing to the public good.”

The suitors all nodded in agreement, praising the duke for his virtue and wit. The patriarch tapped his cane on the marble underfoot in praise of what the duke had said before he shot Belisarius a contemptuous sneer and joined the audience gathering at the duke’s small feet.

Belisarius let his head fall in his hands. Life had been much simpler in his youth. People were straightforward and honest. Plain. Simple. But if he had learned anything from his short time in the palace, it was that the world was full of, and dominated by, men like Stephanakios. How a man as gentle and fair as the emperor made it to the top simply baffled Belisarius, and he was left to wonder if the patriarch was right. They were all a part of the same hypocrisy. Mankind was flawed, and Belisarius had known that as a boy. But he was slowly coming to think that, whether through design or some fundamental misunderstanding of God’s great genius, the more one sinned, the higher he or she would climb.

Belisarius was turning these thoughts over in his mind when a nearby serving slave stumbled and spilled a pitcher of wine across his boots and lap. Belisarius jumped to his feet, regained his composure, and slapped the slave across her face. The girl’s lip broke and bled and she tumbled to the floor with a shriek. The sound of the slap echoed around the garden, and Belisarius became dimly aware that the music and conversation had fallen silent. And, he realized with a creeping sense of dread, everyone was staring at him.

5.

Stephanakios had always admired his father. The elder Stephanakios, who had been named after his father and so named his own son after him, formed his early reputation as a tireless tiger in the fearsome law courts of Antioch. During the last of the Sassanid wars, when the younger Stephanakios served with distinction at the battle of Amida, the elder Stephanakios received the prestigious appointment of first division commander in the Army of the East by then-field marshal Hypatios. When the war ended, the elder Stephanakios went on to serve on the Antioch town council for nearly fifteen years before he passed away at the age of eighty-two. He became a prolific letter-writer in his later years, and two hundred of his most profound and well-regarded epistles were collected and published in a single volume upon his death. The work was rapidly circulated in the aristocratic circles of Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Constantinople, and Latin translations even made the rounds in Rome, Carthage, and other prominent western cities. Therein, the elder Stephanakios mused on everything from his favorite passages of scripture, to whimsical childhood anecdotes, to explanations for certain maneuvers and battlefield decisions he made while serving in the army. The collection received much praise, and fully cemented the old man as a great and honored figure in the minds of his peers.

But the elder Stephanakios had also been a limitless well of profound Stoic wisdom, and wrote close to fifty letters to his son the duke during this period, in which he reflected upon classic Stoic mantras like “Change is Nature’s only constant,” “Love your fate,” and “Remember you must die.” The younger Stephanakios cherished these letters and insisted they be included in his father’s collection. While those essays received somewhat tepid responses from most readers of the work, the duke was pleased that his father’s words would live on to advise and console those of future generations.

So when the duke was torn from his conversation by the awful crack of Belisarius hitting a serving girl, one of his father’s most enduring maxims shot into his head: “Only foreigners and tyrants hit their slaves.”

His father proven right once more, the duke made a mental note to thumb through the old man’s book again before he rose from his chair and sat with Belisarius. The party resumed as soon as the duke left his seat, and Stephanakios allowed a few moments of silence to pass before he opened his mouth.

“Your magnificence,” he said slowly and deliberately, relishing what he was about to say, “I’m not sure what the custom is where you’re from, but we do not hit our slaves here in Syria, much less in Antioch, and we certainly don’t hit slaves that belong to other people. Now since I understand, as I said, that the custom may be different where you’re from, I harbor no ill feelings toward you. I only ask that you do not do it again.”

“I apologize,” said Belisarius. His eyes were wide and fixed on his shoes. “It is not the custom where I’m from.”

Stephanakios was giddy. The boy really was nothing more than some simple half-cooked barbarian. That name, Belisarius, so queer and resoundingly foreign. The duke’s mind gleefully erupted with wild speculation as to which distant heathen race had spawned that awful name. Huns? Goths? A people yet unknown?

“Where is that?” asked the duke, affecting as much charm as he could stomach. “I was just wondering about your name. You’re the only Belisarius I’ve ever met.”

“It was my grandfather’s,” the marshal said quietly. “He was from north of the river.”

“The Danube River?”

“Yes.”

“On the Virgin’s sacred blood! And you pass so well as Roman! I’m the one who should apologize. I misread your race. Please accept my most sincere apologies if I caused you any embarrassment. I should have explained things to you ahead of time. But your language, your style, your dress — an unassuming observer could easily mistake you for Roman. And with how busy I’ve been, it seems I was simply too preoccupied to give your birth or cultural literacy much thought.”

“Thank you,” mumbled Belisarius. He met the duke’s gaze for the very first time. His eyes were pools of dancing amber in the firelight, and for a moment the duke was shocked to see the unmistakable glimmer of Destiny peering back at him. It vanished as quickly as it appeared, and the marshal’s cheeks clenched as he slowly ground his teeth. “But my parents are both second generation. I spent many years in Constantinople. I am a Roman through and through.”

“Yes, I suppose you would think so,” said the duke. “I think it’s marvelous. What a fantastic thing, our commonwealth: a place where even foreign heathen can, in time, wear the honorable mask of civilization. Just think, my friend. In a thousand years, our ships will be on every shore. Our flags on every city wall. Every man who walks the Earth will think himself a Roman, and keep the creed of orthodoxy ready on his lips. Yes, we’ve only seen the beginning of the long arc of our sacred history. If we can make a convincing Roman from your blood within a scant few generations, then the one world city under Christ might soon be a reality. Imagine!”

Belisarius did not join in the duke’s speculation. He mumbled vaguely in the affirmative and then said something about some business that needed his attention before he shot up from his seat and powered off in the garden with that odd, tip-toed way of walking that he had. It took almost all of the duke’s considerable resolve to stop himself from laughing at the sight.

With Belisarius gone, Stephanakios took up his chair again. His guests were filtering away, and the first purple breath of dawn had lit the farthest reaches of the eastern sky. The duke smelled the springtime dew, still sweet and cold from the darkness of the night, and a creeping sense of wonder made him look upon the heavens. That sky; that quiet, empty sky. That same eastern sky Alexander himself had looked upon on countless early mornings all those many years ago. Stephanakios instinctively fingered a foggy silver ring he wore on his thumb, a plain old band marked only with an etching of the chi-rho (☧). His father had worn the ring just as his own father before him. According to family tradition, the ring originally belonged to the duke’s most ancient ancestor: a Makedonian phalangite in Alexander’s army.

As he looked upon the sky, Stephanakios did all he could to picture the progenitor of his line sitting on the ground outside his tent, listening to the distant sounds of Darios and his host fleeing for the vastness of the desert. Stephanakios could almost hear the anguished wails of the camels and oxen as the enemy soldiers dragged them from their sleep, or the ghostly shrieks of the camp followers as they realized they were being abandoned to the hunger of the Makedonians. The duke saw the footmen rising to assembly, a hardy crowd of leathered veterans with tottering sixteen-foot spears balanced on their shoulders. All was aclatter and the men took long, lusty drinks of uncut wine from rough leather sacks. The storm of dust that rose above their towering spears caught fire in the roaring brilliance of the cresting morning sun. The flutists wailed and the drummers beat their skins and the soldiers sang a paean to their ancient heathen gods that kept the tempo of their marching as they fell into place on the plain before the walls and ditches of their camp.

The duke could not imagine the rest. Even though memories of the last war were etched like scars across his mind, the memories he had of the fighting itself were nothing more than isolated flashes of color and emotion. He saw the heathen charge as a solid iron wall with the speed of an eagle falling on its prey. All that weight; all that fury. It was quiet; all he could recall of the sound of their approach was the way it caused his teeth to rattle as those massive armored horses beat the hard dry earth like a drum.

A very dear friend, a boy called Leannatos, was killed in that attack. The two grew up together, studied together, and spent many chirping summer evenings in each other’s company as they hunted wild boars in the hills above the walls of Antioch. When Stephanakios later found him on the field, he identified Leannatos by his curly red hair, a feature so uncommon in that part of the world, and held his ruined body in his arms and cried.

The duke caught his breath. Had those memories always been there, lurking in the shadows of his mind? Had that boy really ever walked the Earth? Had he, the aging man, the duke, really been there, weeping at his friend’s ruined form?

Stephanakios pushed those thoughts away. He was tired. He always mused on regrets and times gone by whenever he stayed up too late. His bed was calling out his name, and he rose and stretched his limbs to heed its lonely voice. Even the slaves had filtered away, and the duke saw that he was, for the first time in a long time, completely and totally alone. There were just the looming palace walls and the crows of distant roosters stirring in the city. Soon the streets would fill with people going about their chores, and the duke’s hazy memories of fear and fallen friends would be buried again by all the noise and necessities of life.

“Remember you must die,” he heard his father say.

Life was far too short to dwell on senseless memories. Only fame was everlasting. This would be the duke’s final war — he knew that much every time his joints creaked and ached. His last chance to seize his rightful share of immortality. And he would make the most of it.

6.

The Romans broke their camp and set out on their march at dawn. Thousands of onlookers crowded the shoulders of the highway, praying and singing as the soldiers marched away. Their footfalls shook the earth as they bellowed marching songs to keep their pace. They moved due south along the orchards and vineyards that circled the city, taking drinks of wine and kisses on their cheeks from the country peasants weeping tears of adoration. The army would keep its course for two days before the highway turned east over the Bargylos mountains, through the Syrian interior, across the Euphrates, and into the ancient lands of Mesopotamia.

Belisarius watched the column pass from the summit of a nearby hill. It was the first time he had seen the field army in full marching order, and as he watched it unfurl along the road below, rank by rank, company by company, its tip and tail both out of view, Belisarius could not fight the sense that he was not a participant in history, but a victim of its whims and a hostage to its course, doomed to simply sleepwalk to his destiny. The dice had been thrown. He was powerless to stop whatever was coming. And as he watched the standards pass, and heard the soldiers sing, and saw their weapons gleaming in the sun, Belisarius knew the cost would far exceed the worth.

The footmen were an ugly patchwork of former slaves, farm boys, foreigners, and thieves, and were some of the hardest men Belisarius had ever seen. Their faces were like beaten bronze and they moved with the swaggering, shuffling, spitting pace of mules. Their many weeks in the fleshpots of Antioch had left them feeling perfectly invincible, and their minds were on the slaves they would take, the coin they would make, and the women they would meet along the road. They swapped lies about all the varied and cosmopolitan pleasures they made use of in the city while they sang old army songs or bawdy country ballads and teased each other like children as they giggled and swore and called the men beside them playful names in hazing jest like “One-Eye,” “Bastard,” or “Gimp Dick.” The sun was up, and God was on their side, and the reality of what they were doing and where they were going was nothing more than a string of strange and senseless words. Lean like hungry dogs, they wore tattoos and ragged beards and gaudy bits of jewelry, and coated themselves in heavy shirts of iron mail and thick dented helmets adorned with dyed horse hair tassels and raptor feathers, each according to his rank. They could sleep standing up, or liked to claim they could, and loudly scoffed at the sissy horsemen who got to go to war while sitting on their asses. They carried oval wooden shields painted with their regimental insignia and eight-foot spears of ash or oak with leaf-shaped iron tips. While many others carried swords, the poorest among them came equipped with bows and wore no armor beyond rotten leather caps and tunics and trousers padded out with wool. One man, much to the marshal’s amusement, marched stark naked, wearing only his boots, ruck, and freedman’s cap. When Constantius caught sight of him, the noseless old mercenary lashed the naked soldier once across the back with his riding crop.

“Where’s your kit, spear?” Constantius barked.

“Come and ask me standing up, candy-ass,” the soldier spat right back.

While their plebeian comrades wallowed in administrative neglect, forced to pass down rusted arms and busted armor straight from the dead to fresh recruits, the cavalrymen were decked out in equipment fresh from the imperial armories in Antioch. Most of these men grew up playing polo on their lavish country estates and sat perched on their mounts with a haughty, privileged air. They wore heavy tasseled helmets and lamellar coats over shirts of mail and overlapping banded iron tubes up and down their arms and legs. Their massive warhorses were similarly adorned in sheets of metal scales that draped down past their knees, and the men came armed with spears, swords, and small round shields. While the footmen slavered at tales of their comrades’ many depravities in the brothels and donkey shows of Antioch, the horsemen talked instead of Homer and the acts of the Apostles, of national destiny and the strange course of Time. They knew each other by their fathers’ names or the feats of adventure they enjoyed in their youthful years at the honored academies they had attended across the Roman world. These patrician warriors cared little for loot or slaves. They measured worth instead by heroism, virtue, and honor, and every man among them ached for a chance to etch his name in the gilded halls of Posterity.

The officers of the field army staff all belonged to the latter caste and accordingly carried all the splendors of power with them on campaign. So while his days were full of all the standard duties Belisarius expected (namely, sitting a horse), the evenings soon came to resemble any one of a thousand palace nights in Constantinople, at which crowds of pale imperial peers gathered in the gilded Hall of Nineteen Couches to smoke opium and listen to performances of esoteric Egyptian poetry while they danced and devised the conquest of the world. Hermogenes soon became the darling of these gatherings, and those silken brigadiers of Antioch sat in rapt and pious silence for hours on end as the Master of the Officers decried petty human weaknesses like love or empathy and praised instead the “supreme immortal virtues” of reason and crusade.

“What is peace?” he said one night in the dancing shadows of the headquarters tent. “If all the many varied races of Mankind were meant to live in total harmony, why would God give us the ability to kill one another, or the passions that inspire wrath? No. Violence is, in fact, our only and most sacred purpose, and Conquest its best vehicle. As soon as Mankind was divided at Babel, God made the reason for Creation plain: it is nothing more than one vast gladiatorial arena, in which his chosen people must fight to earn his affection.”

The brigadiers all crossed themselves and tapped their riding crops on the tables in support of what the eunuch said. Belisarius clenched and unclenched his hands. He felt as if he had wandered into an asylum or some ancient cultic festival in which the real was thrown aside in favor of the reckless passion of the human heart, and the moral orders of eternity were cast away for the bitter chaos of hedonistic oblivion. Their faces were rabid and their eyes were wet with lust for war. Belisarius felt sick. He stood up from his seat. The brigadiers all stood up to attention. Hermogenes uncoiled from his seat with his lips pulled back in a slimy wooden grin.

“That’s enough,” said Belisarius. “This is a war camp. Not one of your smutty garden parties. You’re here to fight. Not talk. Go see to your men. We march at dawn.”

The brigadiers and their virtuous young staff officers frowned and mumbled among themselves but nonetheless still nodded in salute and shuffled from the tent.

The next morning, as the army trundled through the verdant fields of eastern Syria, Belisarius was approached by his chief of staff, a Constantinopolitan senator named Prokopios. The marshal never really cared for him. He was too much like every other bureaucrat and government official who worked in the Sacred Palace: he had that same haughty, blue-blooded strut, the precise attention to rank and title, and the soft hands of an academic. He was not much older than Belisarius, maybe thirty or thirty-five, but his hair was already completely grey. His fingertips were always stained with ink, and he ate little, drank even less, and never seemed to smile. His work was his life, and his self-worth measured by whether men addressed him as “honorable” or “respectable.” He seemed incapable of laughter, or even understanding anything trivial, and struck Belisarius as a bit of a snob. The marshal secretly suspected that the man was a closeted pagan.

“What do you need?” he said.

“My apologies, marshal. I just wanted to say that I appreciate what you said to his magnificence the Master of the Offices last night.”

“Hermogenes.”

“Yes.”

“So say Hermogenes.”

“I appreciate what you said to Hermogenes. You have more allies in your company than you might think.”

Belisarius studied him. Hard black eyes. The distant gaze of a soldier. The simple style and manner of a frontiersman.

“Where are you from?”

“Kaisairia, marshal. Palestine.”

“What’s it like there?”

Prokopios looked out over the fields.

“Not too unlike this,” he said. “But you can stand in the wheat and still hear the crashing of the sea.” He closed his eyes and took a long slow breath. As if savoring the residues of memory. “This is the closest to home I’ve been in nearly twenty years.”

Belisarius followed the Palestinian’s gaze across the fields and saw in his mind the boundless grasslands north of the Danube, where his ancestors hunted game in the way people of the steppe had been hunting since Man first hunted horseback. Sleeping on the ground and sometimes in their saddles but always underneath the stars, they fashioned bows from the horns of their kills and worked the strings with their leathered hands and thickly corded arms as they sang songs older than memory in the campfire light. They drank horse blood mixed with mare’s milk and ate hard black jerky and grasshoppers fried in a pan when there was no game to be found, but when their kills were fresh and abundant they gorged on the flesh like wolves. Yet still their animal gluttony paled in comparison to the appetites of the oligarchs in Constantinople, who ate only for pleasure, or imported rare birds and wines lost on shipwrecks in open displays of wealth. Belisarius knew his years in the palace already made him a foreigner in his own country, and he shuddered to imagine how his grandfather, that stoic old Hun, would think of the man he had become.

“I’ve also not seen home in far too long,” he said.

“Well,” Prokopios said, “If we must fight for something, let it be our homes.”

From that point on, Belisarius chose to ride beside Prokopios, passing long days in the saddle engaged in conversations that mostly went over his head. The Palestinian was a voracious reader of history, and he lectured Belisarius at length about all the invisible curiosities they passed beside the road. A village on the grounds of an Assyrian battlefield. A pig pen where two local saints met their martyrdom. As best Belisarius could tell, it seemed that Prokopios existed in dual realities: the first was the real waking world, full of men and prejudice and chores, and the second was the historical world, the cumulative world, which all Mankind was passing through and adding to with every step. Prokopios understood Time and Creation not as a single straight line from Adam to the present, but instead as a thing that simply was, like a cloud of fog or a bowl of soup, in which all the many parts lived alongside each other, always floating past and always in existence. In the evenings, when the sun dipped within a finger’s width of the horizon, the fields resembled vast sheets of polished copper. Belisarius had always imagined Alexander and the Makedonians pursuing Darios through cruel and barren desert. But suddenly the marshal saw them there, young boys and greybeards, all of them poorer than dirt, marching through a land that seemed to bleed prosperity. He saw them run their leathered fingers through the wheat and shake their heads in wonder as they felt the land’s naked age, and at the countless lives in bygone years who walked upon that very road beside those very same canals and watched that very sun make ancient grasses come alive.

For the first time in his life, Belisarius found himself wondering how much of the story of Mankind remained untold, and how the people of years to come would look upon that place and sun and sky, and stand in wonder at their feeble imaginings of the Romans as they trundled off to war. And then Belisarius gained a dim sense of the fact that the death of any single person was the death of countless unborn nations, and was forced to wonder how many languages, works of art, and marvelous architectural achievements each fallen arrow would annihilate. Lifetimes gone unlived, pale autumn skies left unseen. It was like the felling of a tree: every leaf, branch, and blossom died with the trunk. Every death disfigured posterity. Entire forests of human potential had been ravaged by Alexander and the ambition of his generals. And Alexander died young. Belisarius knew he would die an old man, and that his career was only just beginning. He felt the escalating pressure of the lives and fears of millions driving him toward another historical object of great mass and influence – and their meeting, which had been arranged at the birth of Time, would decide the shape and face of Man forever.

Once all that finished running through his mind, Belisarius pulled over to the side of the highway and vomited.

7.

Stephanakios floundered and failed to remember anything of note that had ever happened in Epiphania. His host, an overweight old bishop named Theophanes, was thrilled to relate the city’s history to the duke, professing himself an avid student of the annals.

“Well,” he sighed with a gentle smile, “the current agora was built in the consulship of Bassus Herculanus and Flavius Sporacius. It was constructed by the prefect at the time, a man called … uh … what was his name?”

Stephanakios supposed that a man of less refinement could be duped into thinking the town was a place of some repute. There was a small stone wall that seemed adequate. The main thoroughfare was swept. There were two theaters, one of which barred the admittance of pagans and Jews. The city’s main basilica was low and plain; an old administrative building. The locals killed stray dogs and street people, so the alleyways were mostly safe and clean.

But Epiphania was not Antioch, which was exactly why Stephanakios had moved his headquarters there from Epiphania in the first place. To make matters worse, peasant farmers and their families were streaming into town from all outlying communities in ever-increasing number, hoping to find some safety hidden behind the walls. This added a chaotic extra layer to the tide of passersby who normally swamped the city: Arabian merchants with long camel trains, bands of ragged pilgrims headed to Jerusalem, and foreign-born Christians seeking work, citizenship, and asylum. While some of the duke’s softer friends might have praised the cosmopolitan character this mixing of peoples gave Epiphania, Stephanakios had about a dozen other words he would rather call the place. Worse yet, a pervasive funk always hung about the town, and Stephanakios was not sure if the smell was something unique to Epiphania or if it was just the average stink common to all Mankind. When he mentioned it to Theophanes, the bishop simply shrugged and scrunched his brow.

“I couldn’t say, your worship,” the bishop said. He tapped his nose. “Allergies.”

Unsatisfied, Stephanakios took the matter to every man he could. The city prefect could not pick the smell out, and neither could the officers on the duke’s own staff. One of the town councilmen thought he noticed something foul, only before he realized that it was a patty of dog shit clinging to his shoe. The priest sweeping the steps of the church could not smell anything out of the ordinary. Out of sheer desperation, Stephanakios even consulted the head of the local Platonic academy.

“A smell?” said the academic.

“A smell most foul,” said Stephanakios.

“By most I assume you mean a smell so foul it surpasses all other smells in its … its what? Its repugnancy? Its atrocity? Its noxiousness?”

“It could not be more foul.”

“That is interesting,” the academic said as he stroked his beard. “But that begs the obvious question: what does it mean to be foul?”

“I feel that’s self-apparent.”

“No doubt. Though not particularly useful in our search for the truth. For what is one man’s foul but another man’s lunch?”

“What?”

“My point being, your worship, that you must give me a better sense of the smell’s qualities, not your judgement of them.”

“It smells foreign.”

“Ah, my good duke,” the academic said, shaking his head with a patient, good-natured smile. “We can’t understand what is foreign without first understanding what is native.”

“You want to know what Roman smells like?”

“It seems necessary before we can answer what does not smell Roman.”

“Well, I smell Roman.”

“So a foreigner is anyone who doesn’t smell like you?”

Stephanakios paused. He supposed the academic did not smell like him. Dry and musty, like an old leather shoe. But the duke could not determine if the academic was a foreigner. His skin was lighter than the duke’s and his beard less well-kept, but the duke knew a number of poorly-groomed and light-skinned Romans. The duke thought the church was all that bound them in their Roman-ness before he remembered there were foreign Christians and Roman pagans, as regrettable as that might have been. He further supposed that he had met a number of well-scented, even personally pleasant, foreigners, and for a few panicked seconds, Stephanakios wondered if all that differentiated what was foreign from what was Roman was an imaginary line drawn somewhere in the open reaches of the eastern desert. But then, realizing the absurdity of such an idea, the duke laughed to himself and bade the academic well.

After all, there was work that needed done, and the duke could not waste all his time talking in circles with some pederastic old hermit. The only problem was that the work that needed done was just as boring and inglorious as Epiphania itself. Paperwork. It all came down to paperwork. Stephanakios could not think of a single toil that was more spiritually vacuous. Action reports occasionally came into his office from around the sector, but most of them were completely banal. They described the movement of caravans, the coming and going of various government officials, rumors of holy portents supposedly witnessed by the lay population, accounting summaries, quartermasters’ audits, the names, ranks, and units of various soldiers dead or incapacitated with disease, and so on. On the rare chance that something of note came across his desk, that information was passed directly on to Belisarius. Sometimes those letters came sealed with wax and string, and Stephanakios had to forward those north without ever even knowing what they said. He knew many of the seals by heart: the dukes of Phoenicia and Arabia were both dear old comrades. Yet their letters always came for someone else’s eyes.

The war was already passing him by, and the real fighting hadn’t even begun. A number of reputable reports already told of a large Sassanid force amassing in Mesopotamia, which Stephanakios would never see. It was far beyond his sector. He could already see the war’s few moves unfolding: Belisarius and his opponent would meet at some frontier town, exchange a few blows, and retire. That might repeat until a clear victor emerged, or the emperor and shah might agree on terms after that first inconclusive meeting. If that were the case, there would be several more months, perhaps even a year, of truce and cold war while the two monarchs kicked the treaty they were drafting back and forth. But the real moves, the grand strategy, the mobilization of peoples, arms, and faith, would have come to an end. And Stephanakios would have to sheath his sword, hang up his armor, and be enslaved again by a life of comfort and anonymity.

“How do you cope?” he asked Theophanes one night as the two sat down for dinner. “There’s a war for Christ and country going on and I’m chained to a desk writing letters.”

“We are honored to have your worship in our presence.”

“That’s all well and fine,” said Stephanakios. “But what’s the point of any of this? Is this really all that life amounts to? I come from a long line of very famous men, your excellence. I have a certain reputation to uphold.”

“What is a good life?” said Theophanes. “I would posit that a good life is not one in which much has been done, but one lived in accordance with Nature.”

“Your excellence, I haven’t come to bandy words about philosophy. I have had more than enough of that lately.”

“There is a line that comes to mind from time to time that goes: a city is not made beautiful by monuments but by the men who call it home.”

Stephanakios knew he had heard the mantra somewhere else before but did not care enough to ask the author’s name. It sounded like much of the same self-congratulatory nonsense that ruined whole generations of men by softening and enfeebling them. Christ was a human god. The leader of a well-ordered Christian life therefore strove for human godhood. One could not achieve salvation by being only good enough. Not when the world was one vast heathen sea, unconquered and uncivilized. Mediocrity had given Epiphania a bishop like Theophanes, whose only concerns were what he would eat and when. Mediocrity had allowed a city as bland and unadorned as Epiphania to exist in the first place. Mediocrity caused the collapse of the western provinces. Half-measures bred no glory. Sloth and self-acceptance would never create a city as grand and everlasting as Antioch, and the commonwealth itself would have been impossible without entire generations of iron men giving their lives and toil to posterity. Now their children, hopelessly vain and self-involved, and too ignorant of the great strain required to build this grand achievement of social engineering, could only sit and watch it collapse.

After some silence, Stephanakios told Theophanes all that he had been thinking. He told the bishop about the sacrifices of their ancestors and the modern softening of Roman youth. How nobody cared for glory or virtue anymore, nor the ancient families who cultivated both. He found himself complaining about the marshal’s savage and provincial nature, and decried the use of heathen troops and the utter immorality of the common marching man. He cursed women and all their witch-like enchantments, as well as the needless abstraction of Homer’s poetry by pagan, sky-headed academics. But most of all Stephanakios cursed his luck — how he, worshipful Duke of Syria, who had broken the Immortals at Amida, son of the great philosopher and statesman who shared his name — how he, Stephanakios, had been relegated to a backwater sector by an incompetent and undeserving commander where his talents would be wasted and where the locals seemed to revel in the rotting of their motherland.

Theophanes watched Stephanakios as the duke ranted about all these and other complaints. The bishop sometimes nodded and sometimes gave a neutral grunt. He never touched his drink. He waved the slaves away. At times he coughed into his napkin, but he never took his eyes off the duke.

“Can I tell you,” Theophanes said after Stephanakios finished, “what I love about this town?”

Stephanakios had worked himself up far too much to care. He just grunted and nodded, shooting down a few tepid dregs of wine at the bottom of his cup.

“This is a place,” said Theophanes, “where the people don’t care for glory or immortality. They are horrified by fame. Here the people care not what they’ll eat, but that they’ll eat, and work not for pay, nor thanks, but purpose. They know and love their neighbors, and are happy with their circumstances. Simple places breed simple people, your worship. But our God was a simple man. And I, for one, am honored to serve him here, among the simplest of his flock.”

“You’ve never wanted more?”

“What is fame? If it were a necessary part of our nature, we would all be known to all at birth.”

Something about the bishop’s smile sickened Stephanakios. He could feel a vastness of wisdom in what the bishop said; the massive weight of an entire ocean of tradition, inquisition, and naked curiosity. If exposed to such a well of sinful knowledge, Stephanakios knew he would at once become a vacant imbecile like Theophanes, blinking in wide-eyed wonder at the poor cutting grass in the fields. He had experienced such a feeling only once before, when a lecturer at the academy in Athens he attended in his youth asked if God could create an object so heavy even He could not lift it. Stephanakios had not followed that destructive line of inquiry then and refused to do so now.

“Well,” he said as he rose and straightened his cloak, “as my father always said: to each their own.”

“Indeed,” said Theophanes, that same fool smile on his fat and greasy face. “Speaking of which, I have always been an admirer of your father’s letters. He seemed a wise and penitent man. And I was delighted to read a fellow student of the Stoics.”

“Yes, he and I both. If you’ll remember, his published letters on the epistles of Seneca were all addressed to me.”

“That’s right,” said Theophanes. “Forgive my … forgetfulness, your worship. I didn’t realize you thought yourself a Stoic.”

Stephanakios frowned.

“Isn’t it self-apparent?”

Theophanes furrowed his brow.

“No,” the bishop said slowly. “I must admit … it is not.”

8.

After crossing the Euphrates, Belisarius and the Romans found that the well-worn highways of the interior quickly gave way to a twisted network of rugged old frontier roads that were poorly kept and rarely paved, and the army’s long trains of supply wagons stalled several times a day because of shattered wheels and broken axle rods. Dust and heat agitated the oxen and mules, and the animals often stopped at the hottest point of the day, ignoring the whips and curses of the men who drove the wagons. The countryside immediately bordering the river was just as lush and green as the hills around Antioch, but tens of thousands of horses’ hooves and wagon wheels quickly turned even the richest earth into a storm of hot dust that reeked of manure and polluted everything the soldiers ate, wore, and drank. The silken brigadiers and all their virtuous young staff officers had stopped dining at headquarters, choosing to take their meals instead with Hermogenes. Rumors of dissent and dissatisfaction with Belisarius and his command floated about the camp, and he went armed night and day and in the company of his bodyguards. No campaign was complete without a general strike among the men, and the marshal feared he would soon have to cross swords with his comrades.

So Belisarius was relieved when, about a month after the army set out from Antioch, the crenelated walls of the city of Daras finally rose upon the distant plains. Built by Anastasios after the last of the Sassanid wars, Daras was designed to withstand and repel a large professional fighting force. But as he neared, Belisarius could see that Daras was far from the fortress city the military manuals made it out to be. The circuit wall had collapsed in several areas, leaving gaps so wide that goatherds from the countryside drove their flocks through the holes on their way to the city cisterns. Many of the homes in the city had also been abandoned, and an earthquake the previous winter had caused half the market quarter to collapse. The locals were all drunk, filthy, and ridden with pox, and starving dogs followed the soldiers everywhere they went, whining for scraps, while girls and boys as young as twelve sold themselves in the agora, charging bits of food or meager coppers for their services.

Bouzes, Duke of Mesopotamia, had repeatedly promised Belisarius that all eight thousand men of the provincial militia would be mustered in Daras by the time he arrived. But the duke had barely pulled together half that number, and those who answered his summons were either beardless and scrawny or crippled by age. The few men who owned any armor beyond their tunics and trousers came in helmets and cuirasses nearly rusted past the point of use. Only a few of these men came out to see the regulars as they settled like a massive flock of migratory birds in the city’s weeded yards and potholed streets. The rest of the militiamen were busy in the only local businesses: the drinking halls and brothels.

The duke himself was a middle-aged man with a paunchy gut and a face scorched and leathered by the harsh eastern sun. His hands and jaw shook from years of rampant alcohol abuse, and he smelled like a dead man walking. The burgundy cloak that marked his rank was mottled and faded, and he wore a pair of ragged old sandals instead of a soldier’s boots. A one-eyed dog followed him everywhere, shedding fleas and patches of greasy fur as it shuffled along, and the duke’s wayward kicks only caused the mutt to bark and gnash its fangs.

Bouzes bowed and kissed the marshal’s ring. Belisarius slapped him across the face.

“You wrote there are fifty thousand Persians at Nisibis.”

“Yes, marshal.”

Belisarius slapped the duke again. He whimpered as his nose cracked and bled.

“You’ve fucked us.”

He pushed Bouzes away, swept his books and papers off his desk and knocked over a nearby chair. Their only other option was to surrender the city and take up a defensive posture on the western side of the Euphrates, thereby handing all of Mesopotamia over to the invaders. Yet in spite of all that, and apparently unaffected by the marshal’s rage, Bouzes just stood there with his mouth half open, blinking slowly like a cow in the sun.

“A thousand apologies, your magnificence,” Bouzes said. “But what’s a man to do?”

“Your fucking job,” spat Belisarius.

So after sticking Bouzes in a small corner office where he felt assured the duke could do no harm, Belisarius set the men to work. Each regiment was assigned to repair a different stretch of fortifications, and while some saw to the wall with fresh bricks and concrete, others dug ditches in between a pair of low hills in the plain before the town. The trenches were arranged in a system of three parallel lines, each about two bowshots long, a stone’s throw wide, and a shovel’s length deep. They were arranged in such a way that two ran in sequence ahead of and parallel to the third, so that the network formed a kind of flattened “V” with the mouth toward Nisibis.

The men assigned to the walls started by tearing down a collection of abandoned buildings and transporting the rubble to their worksites by wheelbarrow and mule-drawn cart. While some mixed concrete in vast copper pots, others put up ladders, pulleys, and scaffolding. As men affectionately nicknamed “mules” dashed up and down the ladders with wicker baskets of rubble slung across their shoulders, the bricklayers, who sweated with trowels in hand and concrete at the ready, worked with the ferocity of sailors damming up a sinking ship. While the ditch-diggers sang and laughed and cursed as they worked, the men on the walls didn’t have the same luxury: if they could not finish their repairs before the Sassanids arrived, they would all be forced to take the field.